Part I – Palmyrene troops in Koptos

Stele of the “Palmyrenians of Koptos”, Roman period Egypt, 1st century, Koptos [Coptos] today Kift / Qift. Two men are wearing a laurel wreaths, keeping wreaths or garlands.

Museum: Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. No. E 501-4 http://collections.mba-lyon.fr/fr/search-notice/detail/e-501-4-stele-d-c8e57

Compilation of all Palmyren reliefs from Koptos – see below.

| Palmyrenians of Koptos , Lyon museum | |

|---|---|

2nd-3rd century 2nd-3rd century Men, wearing wreaths with a central medallion. Holding an ear of corn and a wreath (garland) of flowers http://collections.mba-lyon.fr/fr/search-notice/detail/e-501-3-stele-d-b83bb |  2nd-3rd century Men with a wreath (garland) of flowers http://collections.mba-lyon.fr/fr/search-notice/detail/e-501-6-stele-d-c72a0 |

2nd C Man, Ear of corn http://collections.mba-lyon.fr/fr/search-notice/detail/e-501-2-stele-d-67097 |  2nd-3rd C Men, Ear of corn http://collections.mba-lyon.fr/fr/search-notice/detail/e-501-5-stele-d-2c3f2 |

2nd-3rd C Men, holding a wreath (garland) of flowers http://collections.mba-lyon.fr/fr/search-notice/detail/e-501-1-stele-d-58406 |  1st-2nd C Men, holding a wreath (garland) of flowers http://collections.mba-lyon.fr/fr/search-notice/detail/e-501-7-stele-d-9ecd9 |

Figures (men?) from Coptos’ reliefs are shown bold, holding garlands / wreaths of flowers or an ear of corn.

In Palmyra only priests wearing high modiuses seams to be bold. Wreaths are worn by bearded men, “civilians”, or by priests on the modiuses. Garlands in hand are common to depictions from both places.

Bold priests in Egypt, and beyond, are those of the Isis cult. In Palmyra the relationship of priests with certain cults is not well documented. Only in individual cases are the inscriptions from the reliefs linking the priest with a specific deity. There is not much evidence for Isis cult in Palmyra, but she is mentioned in the dedication[1][2], and her presence as the syncretic goddess Isis-Aphrodite, or in the form of Astarte, is to be proved. It is a part of my private research on symbols shown on reliefs, I argue that some women are depicted as priestesses. As for Isis priestess – the are four reliefs on which women are shown wearing very unique head ornament, crescent with a circle / flower, which reminds the Isis crown. This type of headdress is found only in one more case, in the sculpture from Gandhara (head of Buddha, from Hadda, 3rd-4th century, in Musée Guimet).

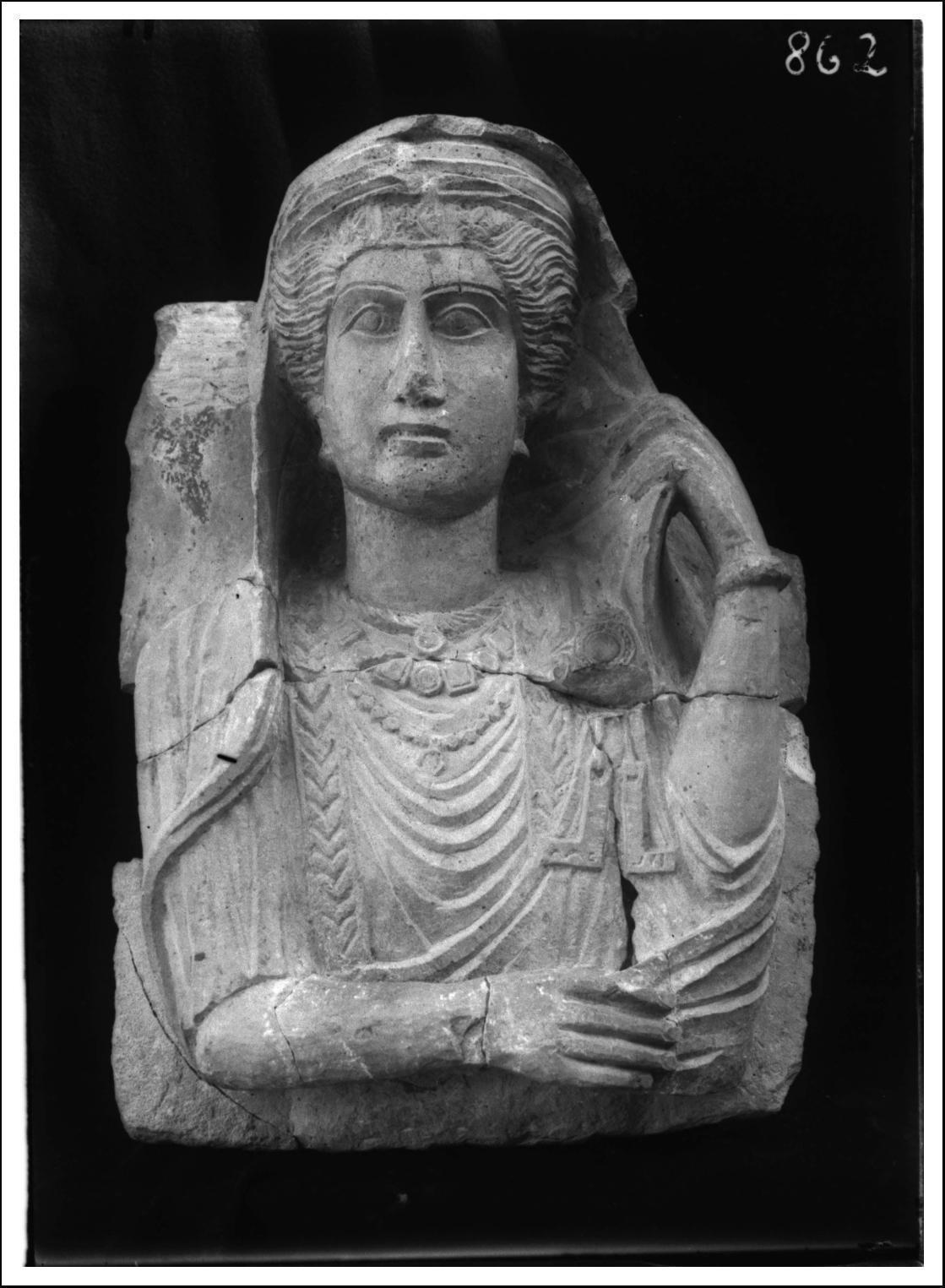

Pic. 1) relief of Batḥabbai, 226 CE, in the Damascus Museum inv. no 9

Pic. 2) relief of Amata, daughter of Zubaida. Musée Archéologique, Strasbourg

Pic. 3) relief of Ba’a from the Hypogeum of Šalamallat, 200-220 CE. The Archaeological Museum of Palmyra, inv. no. 1772/6596

Pic. 4) and 4a) relief of Šalmat and her daughter Hagge, 200-273 CE. In the Museum of Archaeology, Istanbul, Turkey

Pic. 5) Head of Buddha from Hadda, Afghanistan, 3rd-4th century https://commons.m.wikimedia.org

Palmyrene archers in Egypt were present from at least the time of Caracalla (ealry 3rd century) at Didymoi, Dios and Xeron Pelagos. Inscriptions found in Berenice and Koptos mention them. They were deployed in places where the Roman troops have been stationed since 1st-2nd century. [3]

[1] Bulletin d’épigraphie sémitique 1977, Javier Teixidor https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1977_num_54_3_6606

[2] The Basileion of Isis and the religious art of Nabataean Petra; Peter Alpass https://journals.openedition.org/syria/663

[3] Chronology of the Forts of the Routes to Myos Hormos and Berenike during the Graeco-Roman Period

Jean-Pierre Brun https://books.openedition.org/cdf/5239

“Its within this context of international trade and cosmopolitanism that the Aksumite ruler Ezana (r. 330-360) converted to Christianity, after a shipwreck near Adulis brought two Syrian boys named Frumenius and Aedesius into the court of Ezana’s predecessor Ousanas where-after Frumenius gained the favor of the Aksumite king and later his successor Ezana who formally converted in 340AD, Christianity was initially mostly an elite affair restricted to the royal court and prominent members of Aksumite society, but the construction of churches across the empire and the proselytizing work done by Aksumite missionaries spread the religion across the empire’s provinces firmly establishing the religion by the mid 1st millennium.”

Isaac Samuel, The Aksumite empire between Rome and India: an African global power of late antiquity (200-700AD) https://isaacsamuel.substack.com/p/the-aksumite-empire-between-rome

Part II Wall paintings in Ethiopia and Syrian mosaics. Stylistic resemblance.

The paintings of Abuna Yemata Guh church depicting the Apostles on the cupolas, and Moses, Paul, Peter and Thomas among others on the wall and column. The figures are identified by descriptions in Geez calligraphic script that accompany them in accordance with the Ethiopian painting traditions https://www.researchgate.net

Abuna Yemata Guh is one of the nine Saints who are traditionally claimed to have come to Northern Ethiopia in the beginning of the sixth century and established monasteries in the Tigray region[4]. The church, named after him, is a monolithic church situated at a height of 2580 metres and has to be climbed on foot to reach.

“We have, for instance, sound evidence for Syrian influence on the culture of Christian Nubia, especially liturgy. Also Constantinople, a core region of the Eastern Mediterranean and the imperial capital, must be considered as a possible source of inspiration.” [p.6]

The Monasteries and Monks of Nubia, Artur Obluski, 2019 [academia.edu]

- Ex Oriente ad Danubium. The Syrian auxiliary units on the Danube frontier of the Roman Empire

Ovidiu Țentea https://www.researchgate.net - Chronology of the Forts of the Routes to Myos Hormos and Berenike during the Graeco-Roman Period

Jean-Pierre Brun https://books.openedition.org/cdf/5239 - Bulletin d’épigraphie sémitique 1977, Javier Teixidor https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1977_num_54_3_6606

- The Basileion of Isis and the religious art of nabataean Petra; Peter Alpass https://journals.openedition.org/syria/663

- [4]Multi-analytical investigation into painting materials and techniques: the wall paintings of Abuna Yemata Guh church https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40494-016-0101-6

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308691106_Multi-analytical_investigation_into_painting_materials_and_techniques_The_wall_paintings_of_Abuna_Yemata_Guh_church

- https://cultureincrisis.org/projects/survey-of-paintings-in-rock-hewn-and-constructed-churches-in-tigray-ethiopia

- Tigray Churches http://www.ethiopiatravel.co.uk/future-tours/tigray-churches/

- https://www.gettyimages.com/photos/abuna-yemata-guh

- https://nocashonthehighway.com/2019/01/30/adrenaline-and-sheer-rock-climbing-at-abuna-yemata-guh-the-worlds-most-inaccessible-church/amp/

Bibliography from the Lyon museum website concerning the Palmyrenians in Koptos:

Adolphe J. Reinach, “Rapport sur les fouilles de Koptos, deuxième campagne, janvier – février 1911”, Bulletin de la Société Française des Fouilles Archéologiques, t. III, 1912 ; p. 61-64

Adolphe Reinach, Catalogue des antiquités Égyptiennes recueillies dans les fouilles de Koptos en 1910 et 1911 exposées au Musée Guimet de Lyon, Chalon-sur-Saône, 1913 ; p. 46-51, n° 7, fig. 17 et 18

Benoît Fayolle, Le Livre du Musée Guimet de Lyon, Lyon, Vitte, 1958 ; p. 72-74

Henri Seyrig, “Antiquités syriennes n° 102. Le prétendu fondouq palmyrénien de Coptos”, in Syria 49, 1972, p. 97-125 ; fig. 24

Les Réserves de pharaon : l’Egypte dans les collections du Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon, cat. exp. (Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1988), sous la dir. de Philippe Durey, Marc Gabolde, Catherine Grataloup, Lyon, Musée des beaux-arts, 1988 ; p. 88

Aly Abdalla, Graeco-Roman funerary stelae from Upper Egypt, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 1992 ; p. 87, cat. 216

Dominique Brachlianoff, Christian Briend, Philippe Durey et al., Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon : Guide des collections, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux/Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1995 ; p. 35

Egypte romaine, l’autre Egypte (sous la dir. d’Agnès Durand et Gisèle Piérini), Marseille, Musée d’archéologie méditerranéenne, 4 avril – 13 juillet 1997, Marseille, 1997 ; p. 146, n° 166

Geneviève Galliano, Les Antiquités : l’Egypte, le Proche et Moyen-Orient, la Grèce, l’Italie, Guide des collections, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1997 ; p. 49

Coptos : l’Égypte antique aux portes du désert, cat. exp. (Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 3 février – 7 mai 2000), sous la dir. de Marc Gabolde, Geneviève Galliano, collab. Pascale Ballet et al., Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux/Lyon, Musée des beaux-arts, 2000 ; p. 135, cat. 100

Klaus Parlasca, “Zu einigen, zumeist rundplastischen Porträts der Römerzeit aus Ägypten”, Mélanges en l’honneur d’Alcmène Stavridis, Athènes, Ministère de la Culture, 2008, p. 105-114 ; p. 112-113

Vincent Rondot, “Les deux gardiens et le crépuscule des temples. Berlin Ägyptisches Museum inv. 20917”, dans L. Gabolde (éd.), Hommages à Jean-Claude Goyon offerts pour son 70e anniversaire, Bibliothèque d’Étude 143, 2008, p. 345-360 ; p. 346-347

Sylvie Ramond (dir.), Le Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon de A à Z, Lyon, Fage, 2009 (2e éd.) ; p. 73