Inscription:

HBL MLKW BR

DYNYS HNBL

Reads: Alas, Malikû, son of Dionys(ios), (son of) Hennibel

[after Sadurska, Bounni]

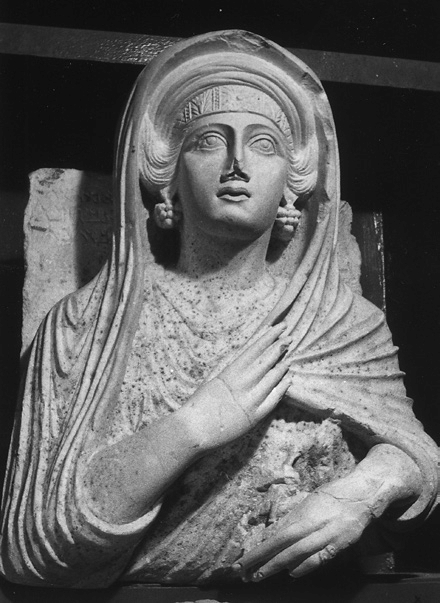

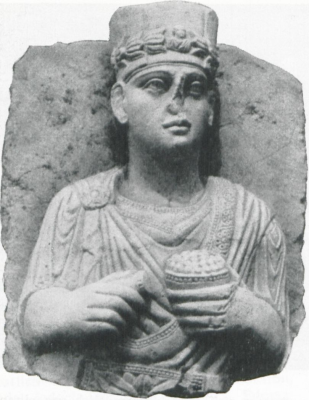

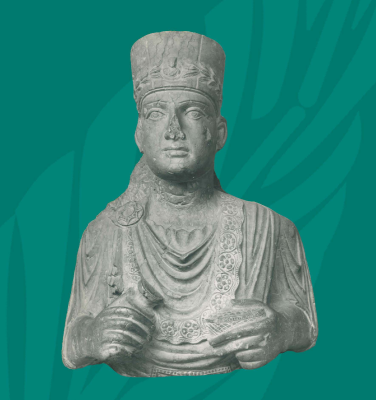

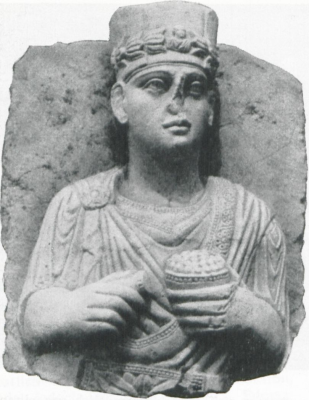

Funerary relief of a priest Maliku [Melko / Milku] found in the tomb of Shalamallat; 120-147 CE. In the Palmyra Museum

Danila Piacentini, La necropoli di Palmira in Siria academia.edu

Anna Sadurska, Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre, Rome 1994, pp. 152-153

“Malikû was the father of Salamallat, founder of the hypogeum, who died before the construction of the tomb (around 120). The portrait is certainly posthumous, executed after the foundation of the hypogeum and before the year 147, when Salamallat in turn died.

Portraits of priests with liturgical vases, carrying a chlamys bordered with an ornament and a wide belt, are quite frequent. The liturgical vases of Malikû are of the usual type in the 1st century.

“Bust of an officiating priest, wearing a simple modius, wearing a short-sleeved chiton and a chlamys fastened to the right shoulder by a round fibula edged with large pearls. The priest holds in his left hand a cup filled with round grains and in his right hand an alabastron. The cup is decorated with a floral ornament. A wide belt with decorated closure completes the costume. The eyes are in two concentric circles, the eyelids delineated, the eyebrows engraved, the chin prominent and the mouth full, regularly drawn. A ring adorns the little finger of the left hand. Note the ornamental border of the chlamys and a decorative band on the sleeves.”

Relief from the Shalamallat [Salamallat] tomb, Palmyra Museum / today Damascus Museum

Representation of a priest with a liturgical vessel.

Anna Sadurska, Die palmyrenische Grabskulptur [https://d-nb.info]

“The male portraits reflect very accurately the development of Palmyra’s social conditions. It is e.g. B. sure that the religious offices were reserved for the social upper class. The priests of the supreme god Baal wore a cylindrical headdress, the so-called Modius, sometimes adorned with a wreath of leaves, with or without a central medallion. They also often held liturgical objects in their hands: incense boxes, perfume bottles or a holy water feather.”

Relief was damaged, and in 2023 restored by the Czech art conservator Eva Míčková from the restoration and conservation workshops of the National Museum in Prague https://www.nm.cz/povinne-zverejnovane-informace/vyrocni-zpravy/vyrocni-zprava-za-2023/sbirkotvorna-cinnost/historicke-muzeum

Circa 150 CE. Palmyra Museum Inv. 2678/8984

Mentioned also in:

Rubina Raja, Representations of Priests in Palmyra: Methodological Considerations on the Meaning of the Representation of Priesthood in the Funerary Sculpture from Roman Period Palmyra; 2016 researchgate.net

Aramaic Inscriptions in the Palmyra Museum. New acquisitions

Khaled Al-Asʿad, Michal Gawlikowski and Jean-Baptiste Yon

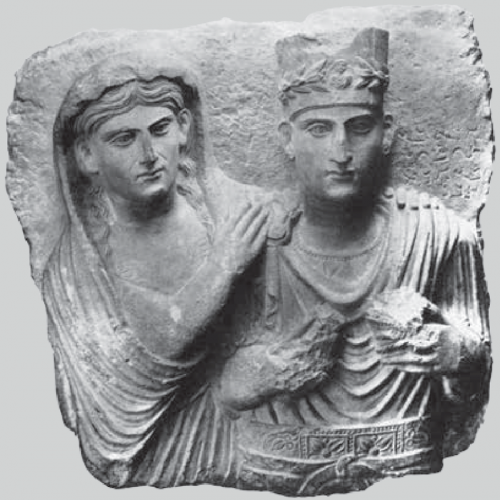

“Funerary plaque with two half-figures of priests holding sacrificial vessels. W. 102 cm, h. 68 cm. On the left a priest with a laurel wreath on his modius, a veil hanging behind, attached on two rosettes with palm branches. The other priest has his face and the front of his modius broken. His right hand rests on the right shoulder of his son.

Found on the grounds of the Desert Police (north from the Museum).

Inscription on the right:

[… b]r tybwl | ḥbl

“- – – son of Taibbol, alas!”

Inscription between the two figures:

rg’ brh ḥbl

“ Raga (?), his son, alas!”

The name rg’ could also be read dg’ (“fowl”), but the former is well attested in Arabic (“Hope”). See Harding 1971, p. 235 and 270, with reference to Littmann 1943, nr. 542.”

Habbûla, Palmyra priest; 50-150 CE; [Museo Barracco]

“Loculus relief depicting a priest. The relief is dated to 50–150 CE.

Museo di Scultura Antica Giovanni Barracco, Rome, inv. no. MB 250.

The inscription reads: “Alas! Habbûla, son of Nesâ. Son of, Yarhibôl”.

Ingholt Archive, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, © The Palmyra Portrait Project”

Rubina Raja

Between fashion phenomena and status symbols: Contextualising the wardrobe of the so-called “former priests” of Palmyra, 2017

In: Textiles and Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean

Palmyra relief representing a priest Zabdila, son of Bar’a, son of Zabde’ateh, holding a libation vase; Palmyrenian inscription. Limestone, dated in Adar 487 (March 176 AD). [Louvre]

Palmyra relief of a priest Tibol, late 2nd C. [BM]

The inscription in Aramaic “The Monument to Tibol, son of Lisaus Tibol the elder, renewed by Aziz, son of Tibol”

In the British Museum inv. no. 125201

Funerary relief of ‘Ogeilu son of’ Atênuri, Palmyra 2nd century.

He wears a wide belt and highly decorated attire.

In the Louvre inv. no. AO 2069

“Funerary relief: man (bust), dressed in two superimposed tunics tied by a belt with a square closure plate and a coat held on the right shoulder by a fibula round, wearing a modius with a vegetal motif adorned in its center with a bust of a man wearing a tunic and a mantle and wearing a modius, holding an alabaster and a round box filled with seeds of incense”

2nd century

In the Louvre Inv. no. AO 4085

Relief of a priest Yaddai, from the hypogeum of Artaban, the southwest necropolis; 170-200 CE

A Report on the Confiscation of Looted Palmyrene Funerary Reliefs in Idlib by simat2017 | Jun 11, 2020

Material: Limestone. Dimensions: 0.51 × 0.46 × 0.27.

General Observations: Minor hairline cracks appear on some of its parts.

“References: Katsumi Tanabe, Sculptures of Palmyra, I (Tokyo 1986), 31, pl. 236; Adnan Bounni, “Palmyre et les Palmyréniens”, in Jean-Marie Dentzer and Winfried Orthmann (eds.), Archeologie et Histoire de la Syrie II” (Saarbrücken, 1989) 251-282, esp. 260, fig. 40a; Anna Sadurska and Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre (Rome, 1994) 26, cat. 19, fig. 83; Maura Heyn, “Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra”, American Journal of Archeology 114 (2010), 655, appendix 5, cat. 27; Signe Krag, “Palmyrene funerary buildings and family burial patterns”, in Signe Krag and Rubina Raja (eds.), Women, children and the family in Palmyra (Copenhagen, 2019), 38-66, esp. 47 n. 86, 63, cat. 67.

Inscription: Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini, Palmyrene Aramaic Texts (Baltimore, 1996), no. 2642.”

Relief of a priest Moqimu, Palmyra; 50-150 CE [British Museum]

Moqimu, son of Gediah, (son of) Ate’aqab the servant.

In the British Museum, inv. no. 125033

Palmyra priest Male and Aqame, his mother (?); Relief dated 150–200 CE, unknown location

»Male, son of, Taibôl son of, Male. Alas! Aqame, his mother«

Source: Rubina Raja, Powerful images of the deceased: Palmyrene funerary portrait culture between local, Greek and Roman representations – 2017 academia.edu

Rubina Raja, Between fashion phenomena and status symbols: Contextualising the wardrobe of the so-called “former priests” of Palmyra, 2017:

“Loculus relief depicting a Palmyrene priest and woman who is holding him. This is a typical mourning motif for

mothers mourning their dead adult children. However, priests seen in constellations with other individuals are rare in the loculus reliefs.

We only know of four. Current location of the piece is unknown.

Ingholt Archive, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, © The Palmyra Portrait Project.”

Rubina Raja, Representations of Priests in Palmyra: Methodological Considerations on the Meaning of the Representation of Priesthood in the Funerary Sculpture from Roman Period Palmyra; 2016

researchgate.net