Edessa / Osrhoene, today Urfa / Şanlıurfa, Turkey. The modern name of the city is likely derived from Urhay or Orhay, the Syriac name of the place before the settlement was founded by Seleucus I Nicator in the Hellenistic period.

After the defeat of the Seleucids in the Seleucid-Parthian Wars, Edessa became the capital of the Kingdom of Osroene with a mixed Syrian and Hellenistic culture. At the beginning of the 3rd century CE Edessa became a Roman colony.

The Kingdom of Osroene, also known as the “Kingdom of Edessa” existed from the 2nd century BCE until the 3rd century CE and was ruled by the Abgarid dynasty. The population of the kingdom, although ruled by a dynasty of Nabataean Arab origin, was culturally mixed and spoke Syriac /Aramaic from the earliest times. The city’s cultural setting was essentially Syrian, alongside strong Greek and Parthian influences, although some Arab cults were also attested in Edessa. After a period under the rule of the Parthian Empire, Osroene was absorbed into the Roman Empire in 114 as a vassal state, then in 214 became a Roman province.

“Edessa was the capital of the small principality of Osrhoene east of the Euphrates and it lay on the great trade route to the East which passed between the Syrian desert to the South and the mountains of Armenia to the North. The city’s inhabitants spoke Syriac, an Aramaic dialect akin to, but not identical with, that spoken in Palestine; and this dialect was the medium of commerce in the Euphrates valley.”

[L. W. Barnard]

the Şanlıurfa Museum

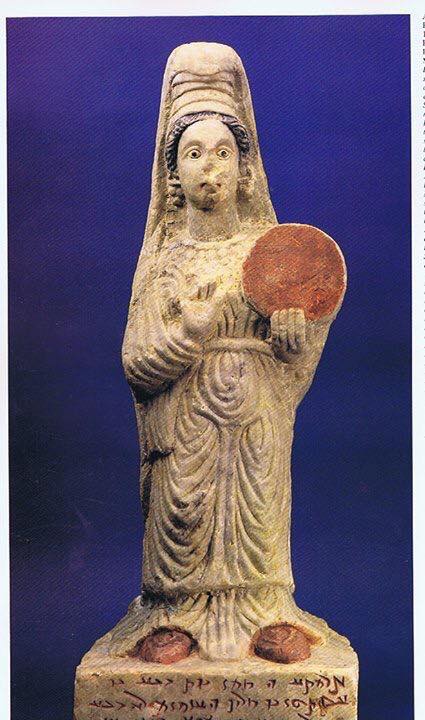

Funerary limestone statue of a man from Edessa, 2nd-3rd century.

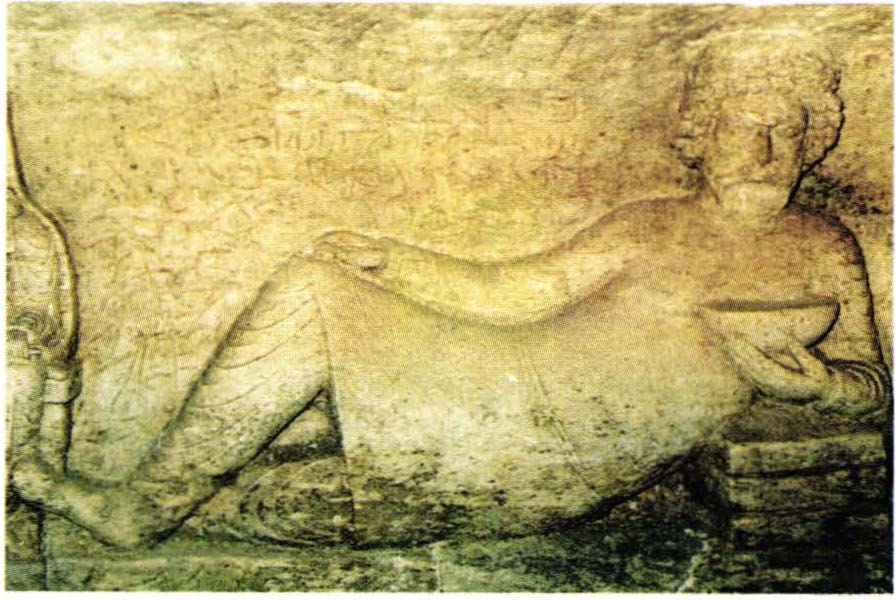

“Apart from the mosaics, workshops in Edessa produced a distinctive group of funerary sculptures. In some of the rock cut tombs, reliefs have been carved in the back walls of the burial niches. They show funerary banquet scenes similar to the funerary banquets in the mosaics. Furthermore, reliefs with busts or full figures of the deceased as well as statues in the round were set up in the tombs. The male statues bear close resemblance to the sculpture of Hatra and, to a lesser degree, the sculpture of Palmyra. They wear loose trousers, long belted tunic with sleeves, a long cloak, and a sword belt and a long sword. Sometimes they are equipped with an additional pair of leather trousers that were used for riding.”

Michael Blömer, Edessa and Osrhoene 2019, in: O. Tekin (ed.) Hellenistic and Roman Anatolia. Kings, Emperors, City States

The rock tombs in the Kızılkoyun Necropolis, two statues of warriors in niches on either side of the sarcophagus tomb. The figures are in the museum today, copies of them have been placed in the necropolis.

The statues of warriors from tomb No. 51 are dressed in Parthian clothes and have characteristic nomadic belts.

Photo source http://www.kulturvarliklari.gov.tr

Photo source http://www.kulturvarliklari.gov.tr

Photo source https://sailingstonetravel.com

Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, The Parthian haute-couture at Palmyra

https://www.academia.edu

the Şanlıurfa Museum

the Şanlıurfa Museum

https://www.sanliurfa.bel.tr/files/1/bsb_sonra/surkav_yayinlari/26_SANLIURFA_UYGARLIGIN_DOGDUGU_SEHIR.pdf

- Michael Blömer, Edessa and Osrhoene 2019, in: O. Tekin (ed.) Hellenistic and Roman Anatolia. Kings, Emperors, City States

- Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, The Parthian haute-couture at Palmyra

https://www.academia.edu - L. W. Barnard, The Origins and Emergence of the Church in Edessa during the First Two Centuries A.D. Vigiliae Christianae

Vol. 22, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), pp. 161-17 https://www.jstor.org/stable/1581930