Wristband with Birds and Palmettes, 800–1000 CE, Thessaloniki, Greece; gold, glass, and enamel; Height 7 cm; Diameter 8.6 x 6.6 cm. Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, inv. no BKO 262/6.

Museum record:

Pair of gold bracelets. Each bracelet is covered by twenty tiles that are defined by granular strips and are decorated with cloisonné enamel. The tiles alternately depict birds pecking at leaves, palms and rosettes and are rendered in different color variations.

http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/art_of_byzantium/

Bracelet [pp. 162 photo; pp. 349 description https://www.academia.edu/Byzantium_Through_the_Centuries]

Византия, Музей Византийской культуры, Фессалоники Инв. № ΒΚο 262/6

“Происхождение: пара золотых браслетов с перегородчатой эмалью была найдена в составе клада в 1959 г. во время археологических раскопок в одном из еврейских кварталов Фессалоник недалеко от порта. Кроме пары эмалевых браслетов, клад включал несколько ювелирных изделий IX–X веков: две парызолотых серег, амулет из золота и стекла, золотой нагрудный крест, золотую подвеску, и 60 золотых монет XVII века (Pelekanidis 1959. P. 55; Antonaras, Gerstel 2016. P. 87–6).

В средневизантийский периодс помощью подобных браслетов закреплялись длинные, доходящие до земли, рукава парадных одеяний. Каждый браслет состоит из двух изогнутых трапециевидных пластин, соединенных двумя шарнирами.Один шарнир имеет стационарную ось, другой подвижен; такая конструкция позволяет открывать браслет. По нижней и верхней кромке браслетов проходит золотой орнамент «косичка». Основное пространство разделено на двадцать квадратов, окаймленных золотой проволокой с шариками (подобие зерни); проволока удерживает квадратные пластинки перегородчатой эмали на золоте, которые и составляют основной декор браслета. На пластинках изображены птицы в профиль, пальметты, цветочные розеткис крестами. Палитра эмалей чрезвычайно богатая, в ней использованы белый, голубой, синий, красный, лиловый цвета. Браслеты из Фессалоник являются единственными дошедшими до нас образцами золотых браслетов с перегородчатой эмалью. Техника эмали была известна уже в классической Греции и широкоприменя лась в ювелирном искусстве Рима; использование эмали продолжилось и в Византии.

Особое распространение получила в IX–X веках техника перегородчатой эмали на золоте. Она позволяла добиваться сочетаний различных оттенков и цветов, которые не смешивались благодаря тому, что каждыйцвет помещался в особую ячейку, границы которой были очерчены золотыми бортиками. При обжигекраски не смешивались, а после охлаждения образовывали гладкую поверхность (Haseloff 1990. P. 32, 33). Благодаря своей изысканности, красоте и высокому уровню исполнения византийские перегородчатыеэмали были необычайно востребованы за пределами империи. Многие изумительные образцы сохрани- лись в сокровищницах и ризницах соборов и церквей Западной Европы; одни из них являлись дарамиевропейским монархам от византийских правителей, другие были трофеями крестоносцев.Данные браслеты занимают особое место в истории ювелирного дела, благодаря и естественнойценности золотых украшений, и утонченным художественным решениям, и искусному исполнению.Они относятся к тем немногочисленным артефактам, которые были непосредственно связаны с высши-ми слоями византийского общества (Pelekanidis 1959. P. 61; Grabar 1962. P. 294; Antonaras, Gerstel 2016.P. 87–96).”

А. Х. Антонарас

“Buried twice over the centuries, a precious gold cuff from Thessaloniki, Greece, is a document of Byzantine history.” https://brewminate.com

An article by Dr. Sharon E. Gerstel / 04.11.2014

Associate Director, Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies

University of California, Los Angeles

Originally published by The Iris under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

“Twice buried and twice revealed, a gold cuff in the exhibition is more than a mere object of art—it embodies the story of a city.

With its mate (shown above), the cuff was found in 1956 in Thessaloniki, Greece, nearly three feet below the ground of Dodecanesos Street, part of the textile district close to the harbor. Buried with the cuffs were two sets of earrings with granulation and pearls, an unusual white glass amulet decorated with red lines and dots, a gold cross that once contained a small relic, and a round gold button. The jewelry may have belonged to a single person, a woman of means who used the cuffs to secure the flared sleeves of her silken gown.

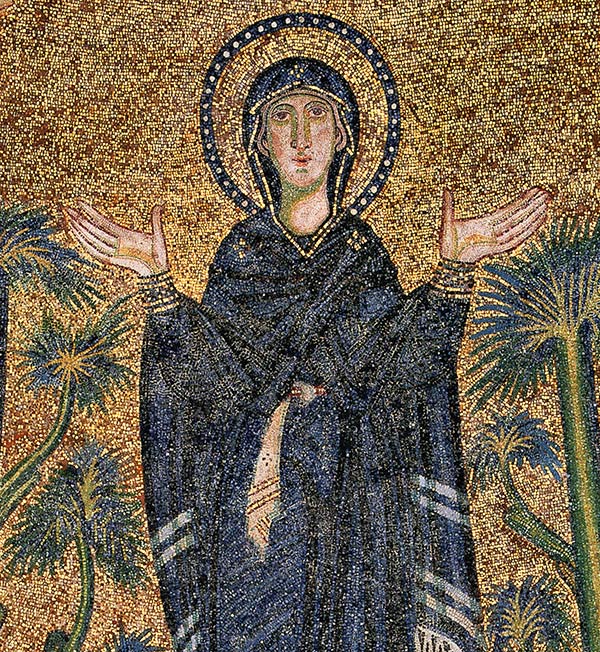

At the time of the cuffs’ creation—the ninth century A.D.—Thessaloniki was a thriving metropolis with a reputation for fine work in gold, silver, precious stones, and silk. The decoration of the dome of Hagia Sophia, the city’s main church, epitomizes the high-caliber mosaic work of the same period. Within the dome, the Virgin Mary wears ornamented cuffs to secure the ends of her sleeves.

Despite their value, however, the cuffs were worn for a relatively short time. On July 29, 904, Thessaloniki was ruthlessly attacked by Saracens. The citizens banded together, dismantling ancient tombs to blockade the harbor. Stone taken from the dead, it was thought, would protect the living. At the same time, the wealthy raced to bury their treasures, hoping to wait out the invasion and to reunite, ultimately, with their valuables. In the course of the invasion the city’s residents were ruthlessly murdered, many as they tried to escape through the city gates.

One witness to the massacre, the church lector John Kaminiates, was spared, but only through his wits and wealth. According to his own words, he promised to reveal to his captors the location of his hidden treasures, warning: “if we die, then that is the end of them: they will to all intents and purposes slip out of your hands and cease to be, along with ourselves.”

The hunt for Thessaloniki’s riches continued for ten days and nights: “with the city yielding an abundant harvest of valuables and other costly finery…so that these objects were piled up on top of one another till they lay in heaps as big as mountains and covered all the ground beneath them.” The cuffs were likely two of many treasures hidden when the city was threatened. Its owner never returned to reclaim them.

Centuries after its burial, the treasure of jewelry was found. Whether through discovery or sale, the pair of cuffs fell into the hands of a new owner, who likely appreciated their fine workmanship, but also prized the base value of their gold. We know this because when the Byzantine cuffs and the other jewelry were unearthed in 1956, they were accompanied by dozens of gold ducats from Venice, Austria, and the Netherlands, as well as a large group of Ottoman coins. This group of valuable objects had been assembled nearly 300 years earlier, about 1660, perhaps by a wealthy merchant.

We will never know the precise reason for the burial of the cuffs, their associated jewelry, and the coins in the mid-1600s, but we do know that this was a time of upheaval for the city’s Jewish community, which was destabilized by the appearance of the pseudo-Messiah Sabbatai Zvi and faced economic challenges due to loss of trade privileges.

The time between the objects’ second burial in the 1600s and their rediscovery in 1956 marked a difficult period for Thessaloniki. In 1917, much of the lower city was damaged in a conflagration that changed the shape and altered the spirit of the city. Buried below the smoldering ashes and debris of Dodecanesos Street was the treasure, covered by yet another layer of history. Safely hidden, the treasure preserves the story of not one, but two owners who never returned to claim it.”