- This Pompeian fresco depicts a Roman woman covered with the typical ball (cloak). National Archaeological Museum, Naples Photo: Scala, Florence

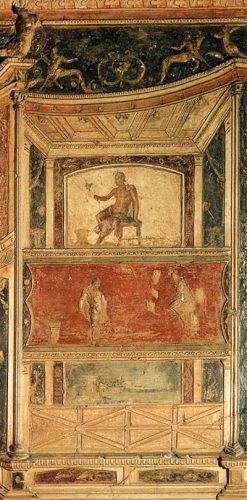

- Pompeian fourth style

THE FOURTH POMPEIAN STYLE from: https://www.romanoimpero.com/2009/12/pittura.html

“The fourth style, known as the “style of architectural illusion”, but also “fantastic style” or “latest style” (almost contemporary to the third).

It was also called “Latin Baroque”, because it was very full and without empty spaces, it was born in the Neronian age, celebrating itself in the sumptuous decorations of the imperial palaces, where the fake architectures, more delicate than the imposing ones of the second style, were characterized by ornaments such as branches plants and miniatures of animals and more.

“It is significant that the only name of a painter belonging to this era transmitted by written sources is that of Studius, who according to Pliny the Elder was the first to invent the very graceful painting of the walls depicting:

– country houses,

– and landscape themes,

– sacred groves,

– woods,

– hills,

– fish ponds,

– canals,

– rivers,

– beaches according to everyone’s wishes,

– and in that environment various types of people who stroll and sail,

– or who go on land to their villas on donkeys or wagons,

– or who fish or hunt or even harvest. Among his subjects also appear – noble country houses, reachable by crossing a swamp, – and women, taken around the neck by paid transporters, who caracol on the shoulders of anxious porters “. The paintings were performed with the fresco technique (on fresh lime plaster with ground colors diluted in water), tempera (the colors were diluted with sticky and gummy solvents, with egg yolk and wax), encaustic (mixing colors with wax).

With this last technique, the painting, once executed, was heated (encaustic) to let the wax penetrate into the colors that thus fixed themselves acquiring strength and splendor.

PLASTERS

The plaster used by the Romans was what we now call marmorino or Roman stucco, or, by mixing colored earths, Venetian stucco. Basically a layer of slaked and pressed and smoothed marble dust to become shiny and compact, taking on an appearance very similar to polished marble.

It could be finished with beeswax to increase its shine and make it impermeable to water, while remaining absolutely breathable. This plaster, already so beautiful, was often frescoed, the same background used for the Renaissance frescoes, and enriched with stucco.

Vitruvius in De Architectura distinguishes the realization of the plaster according to a multi-layer technique:

“The rough coat is applied, a thin preparatory layer of mortar as rough as possible and when it is drying, at least 3 layers of stranded are applied; the first layer of mortar is spread, taking care to adjust the squaring and the verticals of the walls by cutting leveling the plaster before it dries.

When the first layer is in the drying phase, at least two other layers of mortar will be spread in succession, prepared with a part of slaked lime and 2 or 3 parts of sand, taking care to use sand gradually thinner and to decrease the thickness in each subsequent layer reducing it to about half the previous one. “

The thickness of each individual layer could vary from half an inch to a few inches; to improve the adhesion between the first and second layers, the freshly spread plaster could be engraved with a trowel; in the first layer, pieces of bricks or marble were drowned, arranged on a plate or stone chips to increase their solidity and compactness.

The sandstone is the thickest part of the plaster and has a protective function of the wall, to prepare a perfectly flat support for the subsequent plastering.

Subsequently, wet on wet, without waiting for the complete drying of the layer just applied, apply 3 layers of marble obtained using one part of putty and two or three parts of marble dust.

The mortar must be such “that when it is mixed it does not stick to the trowel but easily comes off the iron”.

The ideal is to put as much marble powder as possible while keeping the amalgam easily spread with the spatula; little marble dust will facilitate cracks; too much will prevent the mortar from spreading properly; the successive layers of marble, some mm. thick, they will be gradually thinner and will be worked and smoothed with increasing energy; the last layer will then be beaten with a trowel and smoothed with marble.

With this procedure the plaster will be solid and durable and the colors will shine more; in particular, painting on the last layer of stucco when not yet dry, the color will remain bright for a long time and even washing the wall the colors will not fade; in fact the lime:

“deprived of its humidity in the kilns and having become porous and dry, it quickly impregnates with any substance it comes into contact with and when the mixture dries it becomes a homogeneous block”.

“When only one layer of sand and one layer of marble dust is used, it easily cracks due to its fineness”.

“The stucco therefore, when well executed, does not lose its smoothness by getting dirty and does not lose its color when it is washed, unless it has been given carelessly or if the color has been applied as the stucco is already dry”.

COLORS

First of all there was the sinopia, which was a trace of a reddish color of uncertain composition, once used by fresco painters for preparatory drawings.

The colors were prepared with pigments of vegetable or mineral origin and Vitruvius in De Architectura VII, 7 speaks of a total of 16 colors of which 2 organic, 5 natural and 9 artificial:

the 2 organic:

– black (atramentum), obtained by calcination of the resin with small pieces of resinous wood or of the marc burnt in the oven and then tied with flour; – purple, derived from murex, which was used more in the tempera technique.

the 5 natural ones of mineral origin:

– White,

– yellow,

– red,

– green

– dark tones.

These were obtained by decanting or calcination. Decantation is a technique of separating two substances from a solid-liquid mixture, making the solid deposit on the bottom of the container until all the liquid above is clear. Calcination uses high-temperature heating for the time necessary to eliminate all volatile substances from a chemical compound, used for the production of pictorial pigments, including cerulean.

The nine artificial were obtained from the composition with various substances:

– cinnabar(vermilion red), of mercurial origin, was difficult to lay out and maintain (darkened when exposed to light) and was very expensive (70 sesterces per pound) and highly sought after. It was imported from the mines near Ephesus in Asia Minor and from Sisapo in Spain.

– cerulean (Egyptian blue), obtained with sand crushed with fine nitro mixed with damp iron filings dried and then cooked in small spheres. This color was imported to Rome by a banker, Vestorio, who sold it under the name of Vestorianum and cost about 11 denarii.

The law established that the client provided the “florid” (the most expensive) colors while the “austere” (cheaper) ones were included in the contract. In the shop the master acted with his helpers. These artisans, very dear, were part of the workshop instrumentum and, when the workshop was sold to other owners, they too, together with the work tools (the level, the plumb line, the square, etc.) and with tools changed masters. Their work began at dawn and ended at sunset, and although their works were sought after and admired, they were not held in any consideration.

POMPEIAN RED

It was a color obtained from cinnabar, red lead, earths and iron oxides. According to some scholars, the famous Pompeian red may have been a blue, altered by time. As stated in the chronicles of Pliny the Elder and today Daniela Scagliarini, archaeologist at the University of Bologna.

“Pliny the Elder had written it, but so far he had not given too much weight to that passage in which he says that in the Gulf of Naples the caeruleus or Egyptian blue color was used everywhere, even in the windows”, says Daniela Scagliarini.

In fact, with the physical and chemical analyzes she coordinated herself, it was discovered that there is Egyptian blue in almost all Pompeii paintings.

According to him, the Pompeian color palette should be rewritten. The heat of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD and the wear of time would have altered paintings and mosaics.

The red background walls of the Pompeian houses, for example, were once a beautiful yellow ocher, which with the heat lost its hydration and turned red. While the cinnabar red or “blood red” would turn into dark black. Furthermore, the tiles of the bright red mosaics would become, over time, green in color.

However, the speech is not convincing at all, because the Pompeian red has been found abundantly in the Roman domus, as well as elsewhere. And no volcano has erupted in Rome.”

About pigments:

– cinnabar https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1257007804373762048?s=20

– darkening of the vivid red cinnabar https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1260998135956062209?s=20

– color transformation of yellow ochre into red ochre due to the high temperatures reached during the volcanic eruption https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1278006757030313984?s=20

– Egyptian blue https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1276906057223331840?s=20

– pink https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1268200206551711747?s=20

– black https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1322951799385542656?s=20

- Late Classical and Hellenistic painting techniques https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1281962358542422017?s=20

- “Precious colours” in Ancient Greek polychromy and painting : material aspects and symbolic values https://www.cairn.info/revue-archeologique-2014-1-page-3.htm#

_____________________

1st picture https://www.storicang.it/a/donne-di-roma_14663

See also: THE FRAME BLOG Framing in the Roman Era