An article “Brightly Dyed, 3,000-year Old Textiles From King David-era Found in Southern Israel” by Nir Hasson published >> Jun. 28, 2017 Haaretz.com

“Fragments of woven woolen cloths discovered in copper mines in Timna are among oldest use of true plant dyes discovered in Middle East.

Dozens of fragments of brightly colored fabric from the time of King David and Solomon have been found in an archaeological excavation at Timna in southern Israel, an Israeli research team reported in PLOS One on Wednesday. [June 2017]

The cloths, woven of wool and dated from the 12th century B.C.E. to the 10th century B.C.E., were colored using plant dyes, and some are decorated with a red-and-blue bands pattern. They shed new light on the culture that established the ancient Timna copper mines in the desert, and on the textile industry, during the biblical period 3,000 years ago.

The highly rare textile fragments and their colors were preserved thanks to the region’s extreme arid climatic conditions, say Dr. Naama Sukenik of the Israel Antiquities Authority and Dr. Erez Ben-Yosef of Tel Aviv University, with a research team from Tel Aviv University, Bar-Ilan University, and the Israel Antiquities Authority.

They are the oldest textiles found in the Middle East outside Egypt that were processed with plant-based dyes, say the researchers.

The fragments were small, with the biggest just a few square centimeters in size. The excavation, conducted since 2013 in the area of the ancient Timna Valley mines, is directed by Ben-Yosef.

The dyes were identified at the Bar-Ilan University laboratories using high-pressure liquid chromatography. Analysis found two main sources: madder, used to make red dye from its roots, and indigotin, a blue probably made from woad in a days-long process. Both plants were widely used for dye in the ancient world and were “true dyes,” say the researchers — characterized by chemical bonds between dye and fiber.

Once grown specifically for dyeing in Eretz Israel, their use continued up until the discovery of synthetic colors.

Sukenik suggests that the plants had been cultivated to make dye, attesting to a brisk textile industry, which was located elsewhere. The team thinks the woolen fabric itself was imported to the desert mining area too, which was inhospitable for both sheep and plant cultivation.

Iron Age Timna was principally a copper mining site. Ben-Yosef and Sukenik suggest the discovery of fine, striped dyed cloths indicate that the society at Timna, identified with the Kingdom of Edom, was hierarchical, “and included an upper class that had access to colorful, prestigious textiles.”

Smelting in the ancient world was a highly-skilled task, and previous finds at Timna and the context in which the textiles were found suggests that the metalworkers were among the elite, not lower-class laborers or slaves. In 2014, Tel Aviv University’s Ben-Yosef and Dr. Lidar Sapir-Hen analyzed food remnants from 3,000 years ago and concluded that the laborers operating the furnaces were in fact skilled craftsmen – quasi-magicians – who were held in the highest esteem and dined like lords.

Among other evidence of succulent eating, the archaeologists found bones of fish that had to have been imported from the Mediterranean Sea, not the lowly nearby Red Sea. Also found were seeds of fruit that couldn’t have grown there, including grapes and pomegranates, as well as wheat and barley.

Now the archaeologists speculate that the adulated metalworkers wore distinctive, colored garments. They had to have cost a lot more than plain, undyed clothing.

The people operating the Timna mine belonged to the nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes of Edom. Whether the site was controlled by the kingdoms of David and Solomon in Jerusalem, or Egypt (as has been assumed until this study), remains unknown.

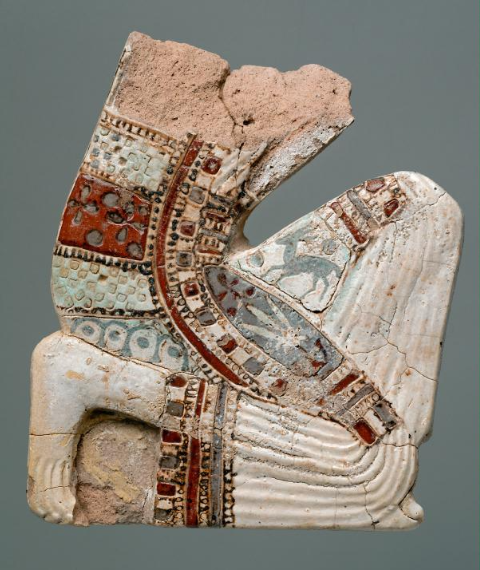

Microscopic magnification (x60) of woolen textile from Timna dyed in red and blue stripes (photo taken with Dino-Lite microscope).

Credit: Dr. Naama Sukenik, Israel Antiquities Authority

Woolen textile from Timna decorated with stripes of red produced from dyers’ madder and blue made from a plant-based indigo that probably derived from wood.

Credit: Clara Amit, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority

Fragments of dyed woolen textile with red and blue stripes.

Credit: Clara Amit, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority

The Timna excavations site Credit: Erez Ben-Yosef, Tel Aviv University