“This delicately decorated shell disc may have been used as a form of personal adornment or jewellery. The interior surface features small holes that could have been used to attach the disc, perhaps to clothing. The shells must have been imported from a coastal area but an unfinished example from the site suggests they were carved at Saruq Al-Hadid.” [The archaeological site of Saruq Al-Hadid https://www.dm.gov.ae]

Such an item could be used as a matrix for making jewelry from sheet metal.

Museum Riyadh, no. 63 F 10

Photo source https://twitter.com/ArabiaBaetyl

Qaryat al-Fāw is considered one of the most important ancient cities in Saudi Arabia, it was the capital of the Kindah Kingdom from the 1st century BCE to the 4th century CE, which was one of the ancient Arab kingdoms in the middle of the Arabian Peninsula.

A Gold Gazelle

“This beautiful gold gazelle was probably once part of

a larger object, perhaps a pendant or necklace. The

gazelle is local to this region and this delightful piece

shows how the jewellery maker was influenced by the

local environment.”

A small sheet-gold plaque from Saruq al-Hadid, Horizon II, depicting a hare or rabbit.

Radiocarbon dates and abundant typological parallels date Horizon II to the early Iron Age (c.1000–800 BCE)

Thaj, South Arabia. 1st century CE burial of a 6 y/o girl

1st century CE royal tomb that was discovered in the summer of 1998, outside the city of Thaj, in northeastern Arabia shows the influence of Greek culture on Northeastern Arabia. Burial belonged to a young girl, about 6 years old, who had been buried in royal manner. A little girl was lying on a funerary bed made of wood covered with lead and bronze and decorated with Mediterranean motifs. The legs of the bed were made in the shape of a female figure depicted in the Classical style.

She was lying on her back, shrouded in cloth, her body was covered with round gold foils, some impressed

with the figure of the god Zeus. Two gold rings were found, set with engraved rubies, one possibly the goddess Artemis and one, the profile of an unknown male wearing a helmet.

A gold mask depicting simple facial features covered her face. Across the top of her head lay three gold bands. On her neck two gold necklaces with rubies, pearls and turquoise (one with a cameo face pendant) and a third

necklace of eighteen gold beads were found. Two gold earrings lay either side of her head, two solid gold bracelets on her left side, a golden glove on her chest and a gold belt across her waist.

More than two hundred convex gold buttons of two sizes, some smaller than the others, lay around her body. Beneath her body lay three large metal vessels, compressed into a single corroded mass and to the right of her head was a small open metal goblet.

The depictions of Zeus and Artemis and other motifs show that this burial dates to the Hellenistic period in Arabia about two thousand years ago. At this time, Arabia was linked into extensive trade routes with the Mediterranean world. Incense from South Arabia was traded along these routes, one of which passed through Thaj. It is this lucrative trade which would have provided the wealth that furnished this grave with such luxurious objects.

The funerary objects buried with a girl — jewelry and adornments, all dated to the first century CE.

A necklace with a medallion from Thaj (1st century CE)

Necklace made of gold with pearls, turquoise, and a ruby cameo. L. 38,5 cm. Diameter of a medallion is 5 cm.

Thāj (Arabic: ثَاج) is located in the northwest of the western region, about 600 km northwest of Riyadh [Tell al-Zayer in eastern Saudi Arabia]. The majority of historians believe that the city of Thāj was built in the period of the Greeks, after the conquest of Alexander in 330 B.C. The most important discoveries in the city were nine stones carved with writing dating back to the middle of the first millennium BC. [https://thereaderwiki.com/en/Ancient_towns_in_Saudi_Arabia]

Photo after Marina Humar

To compare: a gold necklace from Gandhara

Rubies [The side notes]

The Pleasure Gardens of Sigiriya:

A New Approach

Chapter 8 in From Bactria to Taprobane, vol. II

https://www.academia.edu/50839689/FroM_BACtrIA_to_tAproBANe

Osmund Bopearachchi

The island [Sri Lanka] was known to the Indians of the Indus Valley as early as the 4th century BCE. [p. 185]

[p 188]

“Apart from coins, the finding of carnelian and lapis lazuli beads and intaglios, not only at Mantai and Anuradhapura but also from our recent excavations and explorations at Ridiyagama, is of greatest significance, because both categories of stones were certainly imported to the island from North India and Afghanistan.

Carnelian belonging to the chalcedony group is not found in Sri Lanka and was certainly imported from Gujarat, where, according to the archaeological evidence, it was produced without interruption from the early historic period.

It is well known that the reddish colour of carnelian is artificially produced by heating dull brown stones with a high iron content (on the techniques of production of carnelian, see M.L. Inizan, 1991). The author of the Periplus mentions on three occasions that these stones were exported from Barygaza (Periplus, 48-51).

The second category of beads which deserves attention is those made from lapis lazuli, because the only known source for this material in antiquity was Badakhshan (in northern Afghanistan). The author of the Periplus mentions lapis lazuli among the products exported from Barbaricum. This precious material doubtless travelled along the sea route to reach the southern coast of Sri Lanka.

[str 189] The finding of two rings of Greek style in the ancient Greek city of Aï Khanum is of great significance in this regard, because each of them was mounted with a precious stone only attested in Sri Lanka: one with a blue sapphire and the other with a star ruby (O. Bopearachchi and Philippe Flandrin, 2005: 209). One of the most significant contributions towards an understanding of the Greek presence in Bactria was made through the Ai Khanum excavations led by French archaeologists (see P. Bernard, 1982 for a brief description of the site). The site was destroyed by nomadic tribes around 145 bc, so the two rings had reached the Greek city before this date by the sea route, then along the Indus river to Taxila and then to Ai Khanum in northern Afghanistan

[p. 302] Gemstones, especially the pale blue sapphires and rubies for which Sri Lanka had an outstanding reputation in antiquity, were an important part of the eastern sea trade during the Roman and Byzantine periods.”

Gold mask H 17.5 cm, the National Museum of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh, no. 2061.

photo after “Paris 2010”

Gold foil medallion with Zeus

Gold foil medallion with Artemis, diam. 3.5 cm

Photo after Marina Humar

Ayn Jawan Tomb

“At the site of Ayn Jawan a T-shaped tomb of cut limestone ashlars was opened in the late 1940s by several American oil men (Bowen 1950). It was obviously a wealthy tomb, as shown by the jewelry found in it. Furthermore, it lies next to a small settlement of the Seleucid and Parthian periods investigated by the Peabody Museum team in 1977. This grave could well represent the tomb of some petty Parthian royalty, for the jewelry found within it can be compared with a number of Parthian pieces from Iran. Nor is this the only excavated tomb in the area containing Parthian material.” [Daniel T. Potts]

Frontal jewel, 2nd century, gold, semiprecious stones and pearls, length 41.5 cm, from Tarut, the tomb of Ayn Jawan.

Riyadh, Riyadh National Museum No. 1311

To compare

© The Trustees of the British Museum https://www.britishmuseum.org

Gold earrings with Eros linked together by a chain. Cupids holding skyphos, kantharus, pointed amphora and Amalthea’s horn are connected to a garnet inlaid disk. Above the disks are formed the crowns of Isis adorned with emeralds. 1st century BCE

Component height 6.8 cm, chain length 24 cm

2nd century medallion, gold with garnets and pearls.

ø 2.2 cm [M. Humar] Tomb of Ayn Jawan, National Museum, Riyadh.

Photo after Mohammed Mirza

Wall painting with a female figure from Al-Faw, 1st-2nd century. Fragment of a wall painting with a banquet scene.

Black and red paint on white plaster; 58 x 32 cm

Qaryat al-Faw (residential district, sector B 17, 1987 excavations)

Department of Archaeology Museum, King Saud University, Riyadh.

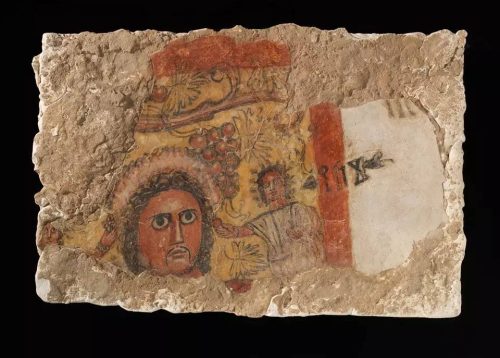

I was struck by the resemblance of this panel from Egypt to the fragment of the wall painting depicting a banquet scene found in Arabia [photo below].

© Royal Ontario Museum https://collections.rom.on.ca/objects/191527

Fragment of wall painting with male head and Old South Arabian inscription: banquet scene (?) 1st-2nd century.

Black, red and yellow paint on white plaster 533×336 cm Qaryat al-Faw, residential district (palace)

National Museum, Riyadh

Fragment of mural painting with zodiacal motif, 1st-3rd century.

Bell earrings, 1st-3rd century, gold, h 3.4 cm, ø ca 2 cm, Qaryat Al-Faw

Bes amulet, 1st millennium BCE

3.8 x 1.5 cm, faience, gold, stone (ruby)

Qaryat al-Faw

Department of Archaeology Museum, King Saud

University, Riyadh, 35 F 8

“Bes amulets were widely diffused throughout the Syria-Palestine area in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age. This Egyptianstyle artefact arrived at Qaryat al-Faw and was preciously preserved there. The magic and apotropaic virtues of this amulet, prized as an antique, were amplified by its gold and ruby setting.”

- Roads of Arabia, Catalogue of the exhibition Roads of Arabia: Archaeology and History of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; Musée du Louvre, Paris 2010

- Daniel T. Potts, NORTHEASTERN ARABIA From the Seleucids to the Earliest Caliphs https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/northeastern-arabia/

- Excavations at Thaj “Tell Al Zayer” (Arabic) [report], Nabiel Al Shaikh نبيل الشيخ https://www.academia.edu/585180/Excavations_at_Thaj_Tell_Al_Zayer_Arabic_

- THE TOMB OF THAJ (Roads of Arabia: Archaeology and history of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Louvre catalogue); Claire Reeler, Nabiel Al Shaikh نبيل الشيخ https://www.academia.edu

- ROADS OF ARABIA 2019, Marina Humar https://www.academia.edu/42475510/ROADS_OF_ARABIA

- Goldwork technology at the Arabian Peninsula. First data from Saruq al Hadid Iron Age site (Dubai, United Arab Emirates)

Ignacio Sorianoa, Alicia Pereab, Nicolau Escanillac, Fernando Contreras Rodrigod, Yaaqoub Yousif Ali Al Alie, Mansour Boraik Radwan Karime, Hassan Zein https://www.sciencedirect.com - Saruq al-Hadid: a persistent temporary place in late prehistoric Arabia

L. Weeks, C.M. Cable, K.A. Franke, S. Karacic, C. Newton, J. Roberts, I. Stepanov, I.K. McRae, M.W. Moore, H. David-Cuny, Y.Y. Al Aali, M. Boraik & H.M. Zein https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00438243.2018.1491324 - The archaeological site of Saruq Al-Hadid https://www.dm.gov.ae

- Recent archaeological research at Saruq al-Hadid, Dubai, UAE https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/aae.12082

- https://gulfnews.com/uae/year-of-the-50th/uae-archaeological-sites-priceless-treasures-of-the-past-1.1606289670467?slide=11

- https://www.une.edu.au/connect/news/2016/04/archaeological-discovery-inspires-2020-world-expo-logo

- SHARP – the Saruq al-Hadid Archaeological Research Project https://blog.une.edu.au

- https://thearabweekly.com/new-dubai-museum-points-iron-age-mysteries

- Pictures >> by Dan Diffendale https://www.flickr.com

- Pictures >> “Roads of Arabia” at the Asian Art Museum 2015 https://genevaanderson.wordpress.com

- Pictures >> https://www.turismoroma.it/en/node/42445

- https://madainproject.com/funerary_mask_of_th%C4%81jite_princess

- Mohammed Mirza Qaryat Al Faw – Arabia’s Forgotten City

- https://www.electa.it/content/uploads/2019/11/ITA_CartellaStampa_Roads_Of_Arabia_definitivo_01.pdf

Women in Eastern Arabia:

Myth and Representation

HATOON AJWAD AL-FASSI

https://faculty.ksu.edu.sa/sites/defau