Astarte, Isis, and Aphrodite

Isis, the Egyptian counterpart of Astarte

“The simultaneous cult of Astarte, Isis, and Aphrodite is also attested at Delos”

“Allat as assimilated to Astarte is without any doubt the form of the goddess that is better documented at Palmyra. The tessera RTP I2I shows on the obverse Bel, Yarhibol, and Aglibol and on the reverse Astarte standing, wearing a long tunic and a polos and holding a scepter. She may be the goddess represented on the ceiling of the great portal of the cella of Bel together with Yarhibol and Aglibol. Similar motifs can be found in the Palmyrene. A stele from the region of al-Maqate’ depicts five deities: Bel, Baal Shamin, Yarhibol, Aglibol, and Astarte. Another stele found in the Wadi ‘Arafa shows nine figures: besides the person offering incense, there are from left to right: Astarte, Aglibol, Malakbel, Bel, Baal Shamin, Nemesis, Arsu, and Abgal”

“they were believed to be the same female deity whom the Arabs called Allat, the Syro-Phoenicians Astarte, the Greeks Aphrodite”

“the statement of Herodotus (3.8) that for the Arabs Allat was Aphrodite Urania”

“The temple of Allat must have been the cultic center of the Arab tribes. The goddess was given the title “Lady of the temple”. […] On these tesserae she is represented as a seated figure with a lion: the camel which appears on both tesserae seems to have been part of the family emblem.”

“The reverse [of tessera] shows Allat seated, with a frontal head and torso and legs turned to the right to accomodate the profile of her throne. She has a lion at her side and holds a bird in her hand, two borrowings from the iconography of Atargatis. A camel is represented in a walking pose in front of her, a motif which arrived at Palmyra from an oriental source”

Javier Teixidor, The Pantheon of Palmyra

2nd-3rd century relief from Palmyra, Syria, with goddesses Allat-Athena and Nemesis, and a donor [dedicator].

‘It / nmys b’ / rb’l ;

(1) ‘Allat

(2) Nemesis

(3)’ Abba ‘

(4) (son of) Rab’el”

Lyon MBA https://collections.mba-lyon.fr

“The imagery on the left side of the relief intimated wealth and social status, whereas the depiction of Astarte and a camel on the right side demonstrated that he was under the protection of one of the most important caravan-goddesses, and thus expresses his loyalty to his local gods (Schmidt-Colinet and al-Asaad, “Zwei Neufunde Palmyrenischer Sarkophage,” p. 275-276).”

Two new finds from Palmyrenian sarcophagi, Andreas Schmidt-Colinet academia

“Archaeological evidence for a cult of Atargatis in the Palmyrene oasis is meager. A text of 132 (BS 45) mentions the temple of Atargatis (‘tr’th) at Palmyra. The tessera RTP 201 shows the goddess accompanied by a hull’s head and a star.

The bilingual inscription of 140 is mentioned below. Other references come from Dura-Europos. This scanty information contrasts with the fervor her devotion aroused elsewhere in the ancient Near East.

The cult of Atargatis, not very popular at Palmyra, must have reached the city from North Syria and must have been preserved as a relic by the Bene Mitha, an Aramaean group, for they had worshiped the goddess under her Aramaean name, ‘attar-‘atteh. In a bilingual inscription of 140the goddess is styled ”ancestral.”

“Atargatis and her consort are represented in a relief from Dura Europos that was found in the debris of her temple there, built during the Parthian period. The two figures are seated side by side, but Atargatis, flanked by her lions, is larger than Hadad. Hadad’s attribute, the bull, is represented at the outside edge at a considerably smaller scale than are the lions”

“A major representation of Atargatis at Palmyra can be seen on a colossal limestone beam of the temple of Bel. One of its faces shows Bel in his chariot charging a monster. The scene is witnessed by six deities, one of whom is Atargatis, identified by the fish at her feet. This artistic tradition can be linked to that of Ascalon, where Atargatis was portrayed as a mermaid (De dea syria 14), or to that of Khirbet Tannur, the Nabataean sanctuary of Edom, where the goddess was usually represented accompanied by fish”

Javier Teixidor, The Pantheon of Palmyra

“The earliest traces of the erotic Aphrodite on Cyprus are the highly eroticized Bird-faced figurines that appear throughout the island in the LC II period (1450–1200). It is clear that the Cypriot Bird-faced terracottas bear a striking resemblance to the nude female figurines of Syria, especially those from the Orontes Valley region. They have in common their nudity, en face posture, jewelry, hair-style, prominent breasts, even more prominent pubic triangles, and, in some instances, the criss-cross over the chest. These Bird-faced figurines appear in Cyprus at precisely that period when there are extensive contacts with the Levant, and when these contacts had a profound influence on the material expression of Cypriot religion. As a result, we might easily suggest that Near Eastern aspects entered into the persona of the eventual Kypris-Aphrodite at this point, and thus there are shades of Ištar and Išḫara in our Cypro-Aegean goddess.”

Transformation of a Goddess, pp. 196-197

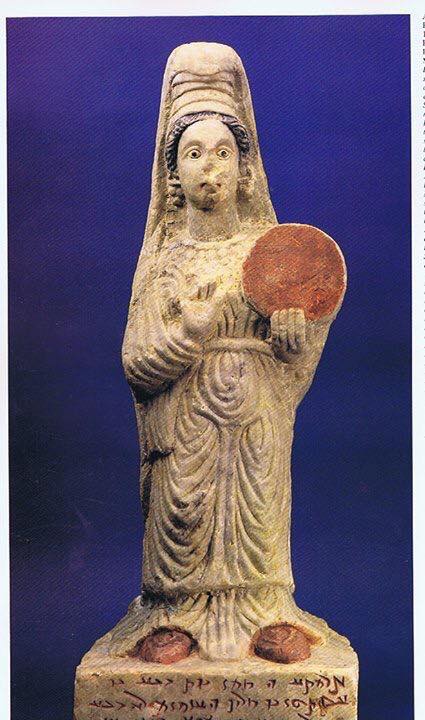

from Phoenician Astarte temple

Transformation of a Goddess, p. 158

wiki

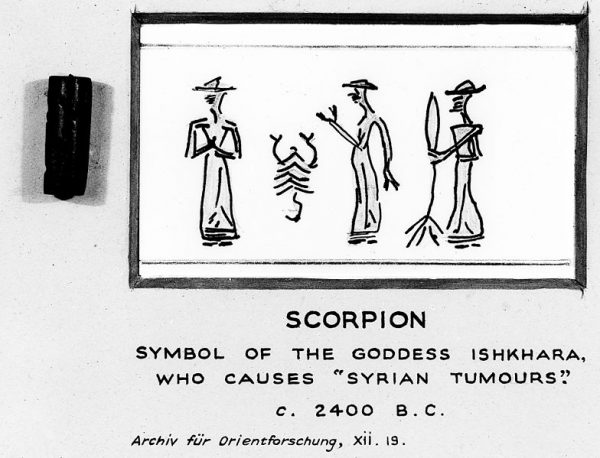

“Ishara (išḫara) is an ancient deity of unknown origin from northern modern Syria.[1] She first appeared in Ebla and was incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon, from which she found her way to the Hittite pantheon.

In Hurrian and Semitic traditions, Išḫara is a love goddess, often identified with Ishtar. Her cult was of considerable importance in Ebla from the mid 3rd millennium BCE, and by the end of the 3rd millennium BCE, she had temples in Nippur, Sippar, Kish, Harbidum, Larsa, and Urum.” wiki

- Jenny Wallensten, Dedications to Double Deities. Syncretism or simply syntax? https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2278

- Javier Teixidor, The Pantheon of Palmyra; 1979 https://brill.com/display/title/1183

- Andreas Schmidt-Colinet, Two new finds from Palmyrenian sarcophagi academia

- Transformation of a Goddess: Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite; Edited by: Sugimoto, David T.; 2014, Academic Press Fribourg, Fribourg Switzerland

- The Scorpion in Mesopotamian Art and Religion

E. Douglas Van Buren https://www.jstor.org/stable/41680288