Hawarte / Hawarti – Syria

“The ceiling was painted five times, as were the walls of the mithraeum. Of the earlier three layers of painting not much can be said, as they are either covered by later layers or found in tiny fragments in the debris. The last but one layer included the name of Mithra painted in large letters”

“The mithraeum was installed in an artificial cave, one of the many to be seen at Hawarte, originally hollowed out for some other purpose. The cave was divided into two rooms by means of a wall of ashlar masonry built inside from south to north. When the construction of the first church over the cave was decided, the first move was to break down the rock ceiling” M. Gawlikowski [2000]

https://pcma.uw.edu.pl/2017/12/09/hawarte/

The first interpretation of this wall painting was “Mithra, his horse and a black prisoner”.

M. Gawlikowski [2000] describes the scene: “There is a huge white horse passing to the right, one of its forelegs lifted. The hoof is partly concealing a four-legged stand or altar, around which a serpent is coiled. In front of the horse there stands a magnificent figure of a man preserved from his waist down. He wears a red tunic reaching to the knees, adorned in front with a band set with precious stones between two vertical rows of pearls. The tunic is passed over his trousers, of which each leg is likewise knit.

This garment is of course well known in Syria, being commonly represented in sculpture from Palmyra. The rich citizens of that city indulged, one century before our paintings, in banquets and hunting parties wearing the kind of costumes that our rider presents. […]

It is clear already that the arms of the tunic were blue and lined with pearls.”

“Indeed, a figure of this stature represented in a mithraeum should normally be Mithra himself. The Persian dress fits the god perfectly, of course. On the other hand, in 4th century Syria, a horse-rider clad in such a way must have inevitably recalled the Persian grandees and the Sassanian king himself. The most striking particularity of this mural is, however, the wretched fellow held on a chain by the heroic figure.

The chain is double, reaching from the hand of the rider to each of the wrists of a Negro, who is entirely naked and shown from behind, crouching. The figure is preserved whole, so it is very clear that the otherwise normal body has two distinct heads, turned in opposing profiles and wearing metal collars on the neck.

What the painter of both murals intended seems not to be simply a search for exotic genre scenes from Africa. The black figures apparently represented some evil forces being destroyed or held in check.” M. Gawlikowski [2000]

Główne pomieszczenie mitreum w Hawarte. W niszy stała rzeźba przedstawiająca tauroktonię (scenę zabijania byka), przed niszą znajdowały się dwa ołtarze.

grota wykorzystywana była przez wyznawców do momentu wzniesienia nad nią kościoła w 421 r.

W Hawarte mitraiści przetrwali tak długo, gdyż ich sanktuarium było na uboczu, zapewne w ogrodzie prywatnej posiadłości – mówi prof. Gawlikowski. Jednocześnie ze znalezionej w grocie ceramiki wynika, że bankiety odprawiano w niej już za panowania Flawiuszy – między 69 a 96 r.

Najstarsze znane dotąd mitreum na Zachodzie (w Germanii) powstało pod koniec I w., a zatem grota w Hawarte jest równie stara lub wręcz starsza. Syryjskie mitreum jest tym samym najdłużej funkcjonującym sanktuarium w imperium, a fakt, że jest być może jednym z najstarszych, poważnie podkopuje teorię o powstaniu mitraizmu w Rzymie.

W sali bankietowej pozbawiona malowideł była tylko nisza – najważniejsze miejsce sanktuarium. Stojący w niej posąg lub płaskorzeźbę z przedstawieniem tauroktonii wyznawcy musieli ukryć, zanim zniszczyli ją chrześcijanie. Oprócz znanych w malarstwie rzymskim motywów (polowanie, winorośl, kosz z owocami) oraz typowych dla ikonografii mitraickiej scen są tu dwie nowości – przy wejściu do sali bankietowej postać w perskim stroju, trzymająca na łańcuchu dwugłowego demona, oraz po lewej stronie niszy miasto demonów zabijanych promieniami Słońca.

– Wygląda, jakby cykl malarski zaczynał się od sceny walki Zeusa z Gigantami, potem są epizody z życia Mitry – narodziny ze skały, spotkanie z Heliosem, taszczenie byka, złożenie go w ofierze – wszystko kończy się pokonaniem demonów. Korzeni tej ostatniej sceny należy szukać w religii irańskiej, która opierała się na walce Dobra ze Złem – to kolejny argument przemawiający za tym, że mitraizm był jednak autentycznym kultem orientalnym – mówi prof. Gawlikowski.

https://www.polityka.pl/tygodnikpolityka/historia/1529045,1,poganski-kult-mitry.read

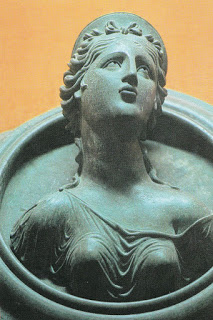

Fragment zrabowanego malowidła przedstawiającego Mitrę i boga Słońca. Homage of Helios

20 marca i 21 września promienie słoneczne wpadające do groty przez otwory w stropie oświetlały ścianę, na której znajdowała się scena narodzin Mitry.

wall topped by various black heads, with rays of light

descending on (or attacking) them. Gawlikowski (2004)

after David Walsh

- Gawlikowski, M. (2000). Hawarte. Excavations, 1999. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 11, 261–273

- Gawlikowski, M. (2001). Hawarte. Third interim report on the work in the Mithraeum, Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 12, 309–314.

- Gawlikowski, M. (2007). The mithraeum at Hawarte and its paintings. JRA, 20, 337–361.

- Parandowska, E. (2008). Hawarte, mithraic wall paintings conservation project. Seasons 2005–2006. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 18, 543–547.

- Zielińska, D. (2010). Hawarte. Project for the reconstruction of the painted decoration of the mithreum. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 19, 527–535.

- Gawlikowski, M. (2012). Excavations in Hawarte 2008–2009. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 21, 481–495.

- Wall paintings from Hawarte & their time. Elżbieta Jastrzębowska https://www.academia.edu/69333994/Wall_paintins_from_Hawarte_and_their_time

- Tomasso Gnoli 2017, Mitrei del Vicino Oriente: una facies orientale del culto misterico di Mithra

- David Walsh, The Cult of Mithras in Late Antiquity: Development, Decline, and Demise Ca. A.D. 270-430